As the country commemorates VE Day: 80 years on, we reflect on the profound bravery and resilience of the South Hams - where the road to D-Day began, and homefront heroes held the line. This now quaint and tranquil part of Devon deserves to be remembered not only for its beauty, but for its immense sacrifice in the fight for freedom.

Brigadier Bernard Law Montgomery

The sea lies still now, lapping gently at the shingle of Slapton Sands but in 1938, whilst the prospect of war was still denied by Government, Brigadier Bernard Law Montgomery recognised strategic potential. He predicted war was on the horizon, and coordinated what would be the first combined forces landing exercise since Gallipoli in 1915. Montgomery's early initiatives laid the groundwork for the extensive training that would later occur in the region, highlighting his role not only as a military tactician but also as a visionary who could anticipate the needs of future warfare.

Evacuation

In November 1943, approximately 3,000 residents were given just six weeks to leave their homes. The region's terrain provided an ideal setting for extensive assault exercises, culminating in large-scale operations. The government's decision, though necessary, meant that families had to abandon homes, farms, and communities, often with little hope of returning to their previous lives.

People were not given an explanation for this sudden evacuation, and needless to say it generated an abundance of problems. Moving the elderly from their homes, abandoning fields the farmers had sown for generations or the possibility of being relocated anywhere in the country with dwindling finances. The Gazette wrote about the evacuation notice on Friday 12 November 1943, and advised readers to handle their comrades with sympathy. And they did. On the 20 December 1943 - every civilian had uprooted all that was familiar without grievance or resistance.

The Cooksworthy Museum, Kingsbridge, is currently running an excellent exhibition named “Six Weeks to Go” which encapsulates memories from those who were evacuated. The top room and their “The Image and The Place” exhibition is rife with information and artifacts that have tastefully immortalised a period in time that is too important to forget.

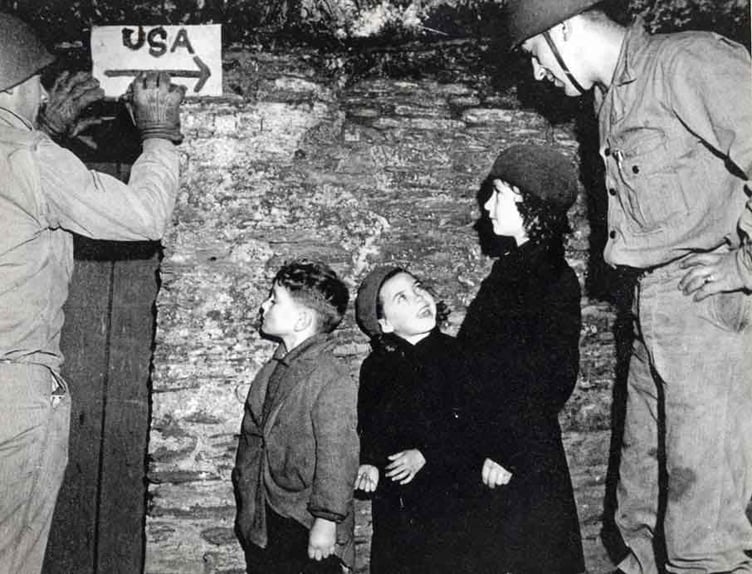

The Yanks

In late 1943, American forces began arriving in the South Hams following the evacuation of civilians from the area. The region's resemblance to the French coastline, particularly Utah Beach, made it a prime location for assault training.

These troops, many from the U.S. 4th Infantry Division, took part in major rehearsals such as Exercise Tiger and Exercise Fabius, both of which were intended to simulate the landings in Normandy. The Americans trained alongside British forces, practicing live ammunition landings, logistics coordination, and beachhead assaults.

Their presence preceded the formal launch of Operation Overlord, which was the codename for the invasion itself on 6 June 1944 (D-Day). The planning stages for Overlord began in early 1943, but troop movements and ground preparations in places like the South Hams started much earlier as part of the Allied strategy to build up strength in southern England.

Their arrival also led to deep cultural and personal exchanges with local communities - a "friendly invasion" of sorts - that is fondly remembered by older generations in Devon to this day.

The Normandy landings are largely considered a turning point in the war for Britain and its allies. The South Hams' involvement in Operation Overlord was both strategic and sacrificial.

Exercise Tiger

In April 1944, Exercise Tiger, a full-scale rehearsal for the Allied landings in Normandy, was held at Slapton Sands, chosen for its close resemblance to the actual invasion site in northern France.

The exercise involved around 30,000 American troops and was meant to simulate every detail of the D-Day landings - from loading tanks onto landing craft to storming the beach under live fire. British and American forces coordinated the complex logistics, with Royal Navy vessels patrolling Lyme Bay to protect the training convoy.

In one phase of the exercise, live ammunition was used to prepare soldiers for the realism of combat. Miscommunication and delays in landing times meant some troops came under fire from their own side.

But in the early hours of 28 April 1944, the operation took its most tragic turn.

A convoy of eight American LSTs (Landing Ship, Tank), slowly making their way toward the beach, was ambushed by nine German E-boats (fast torpedo boats) that had slipped past the Royal Navy escort. The convoy was vulnerable: due to miscommunications, one of the two British destroyers meant to escort the convoy was not present, and the American forces were operating on different radio frequencies, unable to warn one another in time.

In total, 749 American servicemen lost their lives - 197 Navy sailors and 552 Army soldiers - making it the deadliest training accident of the entire war for the U.S. military. Many drowned in the cold waters of Lyme Bay, others were killed by hypothermia or fire from the explosions.

The magnitude of the disaster was initially classified as top secret. With D-Day fast approaching, Allied commanders feared the incident would compromise morale or tip off the Germans about invasion plans. Survivors were ordered not to speak of what happened. Many carried the trauma in silence for decades.

It wasn’t until the 1970s, largely thanks to the efforts of local historian Ken Small, that the story gained public attention. Small recovered a Sherman tank from the seabed - now displayed at Torcross as a permanent memorial - and worked tirelessly to honour the men who died.

Today, Exercise Tiger is remembered not as a failure, but as a solemn reminder of the price of preparedness. The lessons learned in that tragic night led to crucial improvements in communications, landing protocols, and equipment distribution - changes that saved countless lives on D-Day.

RAF Squadron 610.

While soldiers trained on beaches, another battle raged far above. The skies over Britain were watched, protected, and fiercely defended by the Royal Air Force - among them, the legendary RAF Squadron 610, the “County of Chester Squadron.”

Though not permanently based in the South Hams, 610 Squadron was deployed across Southern England, including periods of service in the South West. Flying the iconic Supermarine Spitfire, the pilots of 610 were part of Fighter Command’s front line during the Battle of Britain in 1940.

Pilots from the squadron often flew out of bases in the wider region, including RAF Exeter and RAF Ibsley in Hampshire, both strategically close to the South Hams coastline. When based nearby, the young airmen would occasionally mix with local people, finding fleeting moments of warmth and humanity between missions.

With thousands of Allied troops assembling across the region and large-scale operations like Exercise Tiger unfolding along the coast, the skies above the South Hams were far from safe. German surveillance aircraft frequently probed the coastline, and the threat of E-boat activity in the Channel was constant. Pilots from 610 Squadron were scrambled to intercept enemy aircraft and patrol the airspace, ensuring the secrecy and security of the preparations for D-Day.

By the end of the war, the squadron had flown thousands of sorties, claimed hundreds of enemy aircraft but most of Squadron 610’s original members had been killed in action - many of them young men in their teens and twenties. Their greatest legacy lies not in victories tallied, but in lives saved - both in the air and on the ground. Their sacrifice was enormous, and their legacy immortalised by Winston Churchill’s words: “Never in the field of human conflict was so much owed by so many to so few.”

The Women’s Land Army

With many men conscripted into military service, the Women's Land Army (WLA) became the backbone of agricultural production in the South Hams. These women toiled tirelessly in fields and farms, ensuring that the nation remained fed.

Their efforts became especially vital during the evacuation and training periods, as they managed the land left behind and supported the logistical needs of incoming troops. They became a lifeline for both agriculture and morale.

With its rich farmland and dairy heritage, the South Hams played a vital role in feeding the nation. The abrupt evacuation of villages like Strete, Slapton, Blackawton and East Allington meant that many fields were left untended. The WLA stepped in with determination and strength. Often called “Land Girls,” these women signed up with little experience but a fierce willingness to work.

At Bugford Farm near Blackawton, WLA members maintained dairy herds while the local men were away and oversaw lambing season during harsh winters. In Stoke Fleming, Land Girls helped salvage food supplies from evacuated properties and ensured livestock left behind was fed, earning the admiration and gratitude of locals.

Beyond their work in the fields, many Land Girls played a quiet but crucial role during the 1943 evacuation of the South Hams. As families packed up generations of life in just a few weeks, members of the Women’s Land Army helped coordinate relocations, offered temporary shelter, and even helped resettle livestock and pets. Some worked with local councils to identify spare rooms and farms willing to host evacuees, while others simply opened their own lodgings.

Despite facing hardship, sexism, and grueling labour, the women of the WLA remained steadfast. By the war’s end, they had proved not only that women could carry the burden of wartime farming, but that their contribution was vital to victory. A quiet army in muddy boots, they kept the country fed, the farms alive, and the South Hams fields thriving.

Kingsbridge & Salcombe Water Board

Even the water board of the time were involved in the war effort, supplying landing crafts harboured at Salcome that were destined for Normandy beaches. Some of the crafts required as much as 450 tons of water (approximately 457,000 litres). As a result, the reservoir at Blackdown reduced from its normal depth of 10ft, to a mere 18 inches.

A critical meeting was called with American Naval authorities who agreed to install a booster pump. Councillor R. E. Morris, said this act “saved the situation” and ensured the continued supply of water to the district.

RNLI

The Royal National Lifeboat Institution (RNLI) played a largely unsung role in the war effort, despite launching 3,760 lifeboat missions between 1939 and 1945. In doing so, they saved an astonishing 6,376 lives - a testament to their unwavering courage in the face of peril.

Lifeboat crews, made up of local volunteers, were called to assist not just stricken merchant vessels, but ships carrying explosives, troops, and classified military intelligence. They braved enemy fire, navigated mined waters, and launched in all weathers to rescue downed airmen, tow disabled craft, deliver food to cut-off communities, and bring doctors to the injured and priests to the dying.

Perhaps the most poignant moment came at the very end of the conflict. Just one minute before peace was declared, the Salcombe lifeboat launched for the final rescue of the war, responding to a Norwegian minesweeper that had struck an explosion off the Devon coast. The Torbay and Salcombe crews searched the sea in vain; only two floating cushions were recovered. It was a final act of selfless service in a war that had already demanded so much.

Twelve lifeboat crew members lost their lives during the war, and seven RNLI lifeboats were lost, some destroyed in air raids, others captured or wrecked. Yet their legacy is written not only in numbers, but in the quiet heroism of every launch - and the countless families reunited because of their devotion.

Eighty years on from VE Day, the South Hams stands as more than a postcard-perfect corner of Devon - it is hallowed ground, shaped by extraordinary acts of courage, loss, and endurance. From the quiet sacrifice of evacuees and the tireless labour of Land Girls, to the Allied soldiers who trained for D-Day on its shores, this region played an unspoken but vital role in securing peace. The tragedy of Exercise Tiger, the watchful bravery of RAF pilots, and the lifeboat crews who answered every call remind us that war touched every tide and hedgerow here. Brigadier Montgomery’s foresight and the collective will of a community under strain forged a legacy that echoes through the decades. On this anniversary, we do not just remember victory - we honour those who made it possible. The South Hams was not merely a backdrop to history; it helped shape its course.

“We shall have failed and the blood of our dearest will have flowed in vain, if the victory which they died to win does not lead to a lasting peace” - His Majesty King George VI.

Comments

This article has no comments yet. Be the first to leave a comment.